When we have to find our way in built environments, a dialogue between ourselves and the building emerges. This dialogue can be enhanced by designers, architects and planners through different architectural interventions to support orientation and wayfinding.

But what actually happens when finding one’s way? And how can we facilitate and make this process as easy and intuitive – for as many as possible, regardless of abilities and preconditions – through design? This was investigated by Triagonal through a study of evidence-based literature on how people orientate themselves in, and navigate, places.

How can we design inclusive wayfinding for all?

Want to know more?

Most of us have experienced standing utterly confused in the lobby of a hospital or in an airport terminal, looking for information. We know where to go to – we might have the number of a specific hospital ward or a gate – but how do we get there? Applying a more profound understanding of how human beings orientate themselves and navigate it is actually possible to design spaces where most people easily find their way – irrespective of their capabilities. Using design and architectural interventions the dialogue between the individual and its physical surroundings can be enhanced. If we deliberate this dialogue when we design spaces, we minimise the need for adding wayfinding as an extra layer of information. Where the complexity of a building requires clear and concise navigation the same concerns can be applied to the design of wayfinding strategies that pay respect to the uniqueness of the space and its architectural qualities but also to the users of the space and their individual needs.

The wayfinding loop

In their endeavours to find their way, individuals enter into a dialogue with the space they are navigating. A process termed “the wayfinding loop” by researcher Muna Al Ibrahim¹ occurs. First, often unconsciously, we scan our surroundings for cues that can give us a hint about where we are going. A cue can be an actual sign. But it can also be the outlook through a window or a large memorable pillar in the in the middle of the room that helps us understand where we are in the building and where to go next. Then, we move in the direction we assume to be right. As we move along, we gather new information that either confirms that we are on the right track or indicates that we have to change directions. Hence a continuous circular process between planning and executing takes place until we reach our intended destination. The surrounding space communicates with the user via cues from the architecture and interior design while the user interprets the cues based on previous experiences and capabilities.

The relationship between the built environment and its users

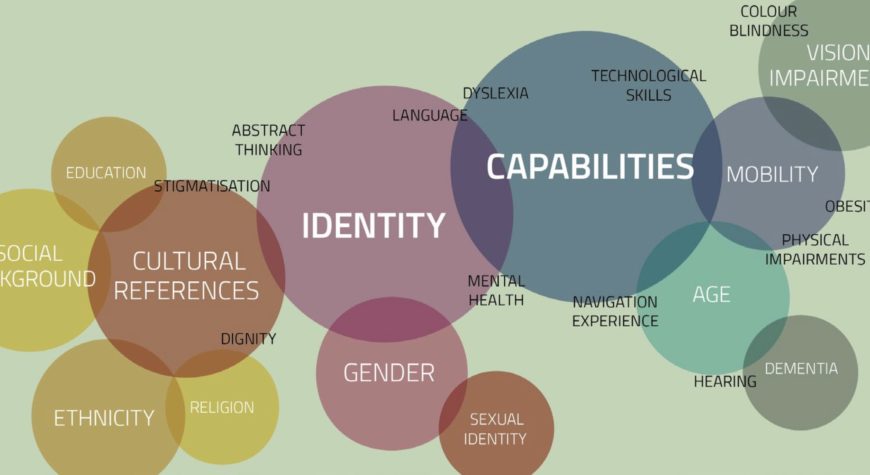

Understanding the dialogue that arises between the space and the user enables designers, architects and planners to make navigation in complex spaces easier and more intuitive for all, irrespective of their abilities and preconditions. This can be done by supporting the interaction between the personal and physical factors as illustrated in the model above.

By utilizing factors like sightlines and landmarks we can support the user’s navigation, improve the overall visibility and orientation and make important destinations recognisable. Visual access to your destination makes any extra information to find your way superfluous. A more carefully conceived layout and more conscious deliberations of the interior design can contribute to spaces that are visually more diverse and easier to distinguish from each other. Large buildings like hospitals and airports are often particularly complex due to their size and unvarying interiors. When buildings are undistinguishable by design it is harder for users to know whether they are at the right place or not. Adding elements that contribute to variability and memorability is one way of making spaces easier to orientate within, without increasing the complexity of the floor plan or the number of decision points². Such variations in the design become part of our mental overview – our cognitive map – of the space.

This cognitive map in turn becomes more and more detailed as we gain more information about the space. It is the ability to create cognitive maps that enables us to remember the route to a destination by heart without relying on signs or maps, placing confidence in the memorable elements of the space. Such elements can be designed specifically to contribute to the overall impression of the space while at the same time supporting the users’ navigation³.

Moreover, creative use of interior design can add another way-showing layer e.g., using lighting, furniture or other designed elements to nudge users to choose certain routes hence creating specific, desirable flows through the space. The names of various destinations should also be taken into consideration as distinguishable names communicate directly to the users. Latin terms can be meaningful to medical professionals, but are rarely understandable to the majority of users who are actually the ones in most need of assistance in relation to wayfinding.

All the above are architectural interventions that can facilitate navigation in built environments without adding signs, and yet improving the signs of usability or “affordance” of the space as it is termed by psychologist James Gibson⁴. All things bear in them signs of usability, a kind of invitation to how they should be used. A teapot with a handle and a spout invites you to hold the handle and pour from the spout – it has a clear and recognizable affordance. As designers we have the opportunity of shaping the affordances of things and spaces to make them trigger a certain use or behaviour.

The teapot can, however, also be used as a vase if that is what the user is in need of even though this might not be the use intended by the designer. In this way the user’s interpretation of the affordances of a space correlates with their individual abilities, experiences and perspectives.

Some have been flying to foreign destinations for summer holidays with their families for years and know exactly what to expect when they arrive at the airport and what their “user journey” will look like. Others might never have set foot in an airport before but are used to navigating other complex environments and have built up their experience with wayfinding and orientation in this way. For others, e.g. with only partial or no sight, the experiences from similar situations might be characterised by other stimuli. Light and shiny surfaces for example will often be interpreted as windows based on previous experiences⁵. Experiences like these contribute to shaping our expectations to what it will take to find our way. Our experiences and expectations also affect our emotional state depending on whether we had good or negative experiences in similar situations in the past.

Wayfinding for All

Everyone can experience a certain level of challenge and stress when it comes to finding their way in an unfamiliar space for the first time. Adding to that, different cognitive, emotional and physical limitations can affect people’s ability to orientate themselves and receive wayfinding information from their surroundings. Especially in hospitals people can be emotionally affected by what is awaiting them. These emotions affect our ability to focus, orientate ourselves and take in new information. If, on top of this, if there is little help to be found in the environment to help us find our way we become even more emotionally affected. Therefore, it is important that spaces are designed to clearly and intuitively communicate to as many users as possible in line with the principles for universal design. Keeping an eye on the users’ needs and behaviour, designers, architects and planners can design spaces and wayfinding where the affordances of the space are clear and intuitive for as many users as possible while at the same time inviting a behaviour that supports the function of the space. When we succeed at this complicated task, we reduce the feeling of stress for users and thereby create a sense of safety and comfort, hence improving the overall user experience.